A common question we get here at the Great Library is: “If everything is now online, why do you need to keep these musty old books?” While it would be nice to assume that everything you need to know is available online through Google or a quick query to ChatGPT, you shouldn’t disregard the older editions of texts and their tables of cases that can be found in our often overlooked 1st floor and extensive closed stacks.

Back in 2016, a group of Canadian law librarians discussed the concept of lost law; the idea that older case law tends not be cited in newer editions of texts and may potentially disappear. This case law could still be relevant in the present day, but without citations, they might be harder to surface. This led to a discussion of older editions of texts and the justifications for keeping or withdrawing them from library collections. Since space is at a premium for many libraries, it is fortunate that the Great Library is able to provide access and preservation to outdated (but still relevant) materials.

At this point, you may be saying to yourself, “that’s all well and good but I don’t care about older decisions so why would I look at superseded editions of texts?” Older secondary sources not only provide access to older decisions but also show the overall evolution of an area of law. The Great Library strives to keep all superseded editions of seminal texts for both the UK and Canadian jurisdictions.

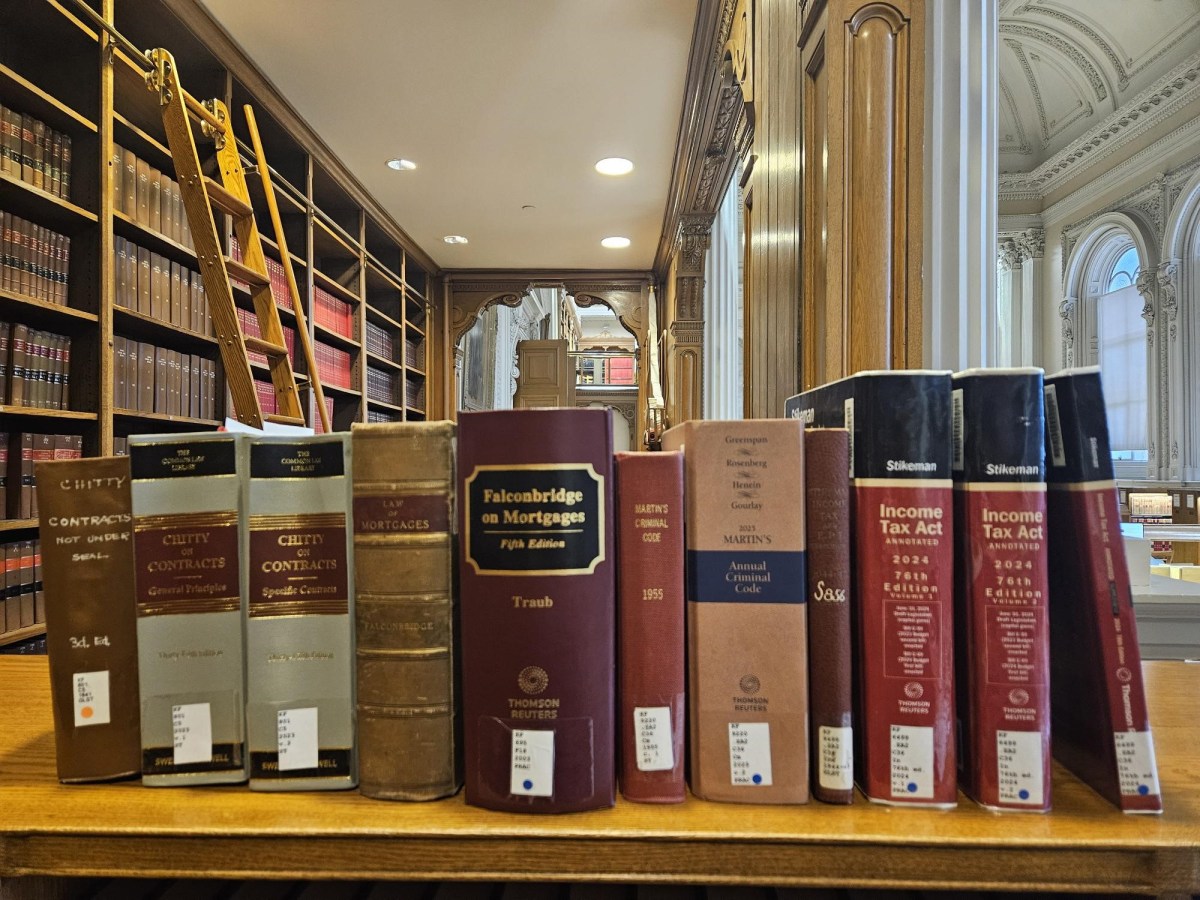

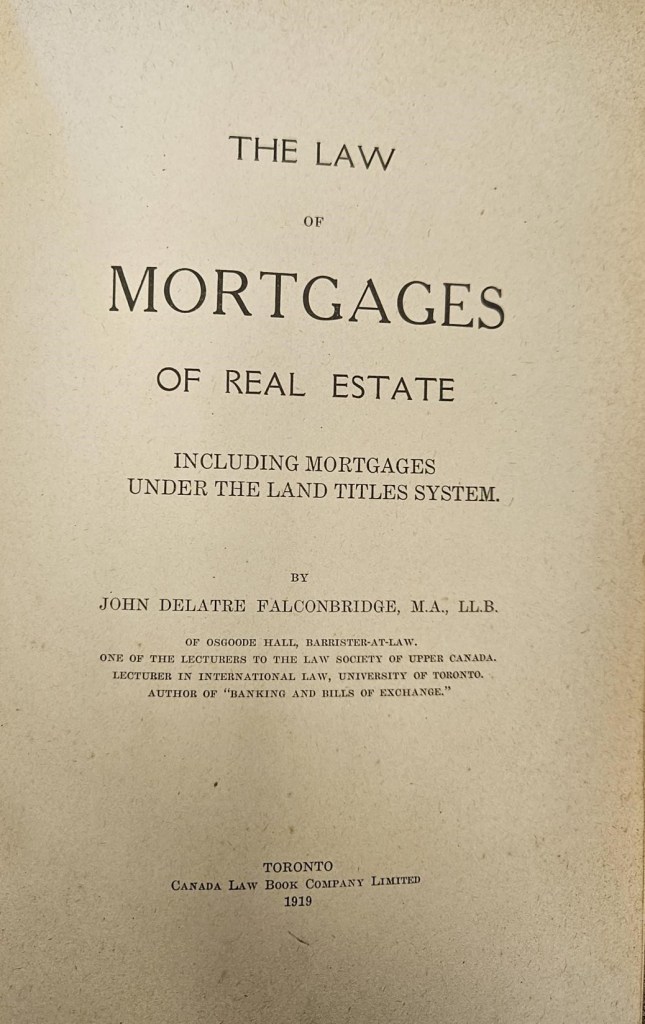

A good UK example is Chitty on Contracts, whose 1st edition was published in 1826 and the 35th (and most recent) edition was just published in 2023 (an almost 200-year run and counting)! While we do not have the 1st or 2nd ed. in our collection, we have every other edition from the 3rd to the 35th. Falconbridge on Mortgages, an important Canadian text, has been running for a respectable 105 years and counting. We have all 5 editions of this text in our collection.

You never know what could be hidden in these old editions. We recently had an articling student come into the library looking for a policy made under the Planning Act from the 1990s. It pre-dates digital publication, and we couldn’t find it on any archived government website. Instead, we turned to some of our old Planning Law texts in the closed stacks that were published around the same period and – lo and behold! -we found a reproduced copy published in an older edition of a text. When trying to find outdated or superseded policies, guidelines, and bulletins for point-in-time research, older editions can be unexpected treasure troves.

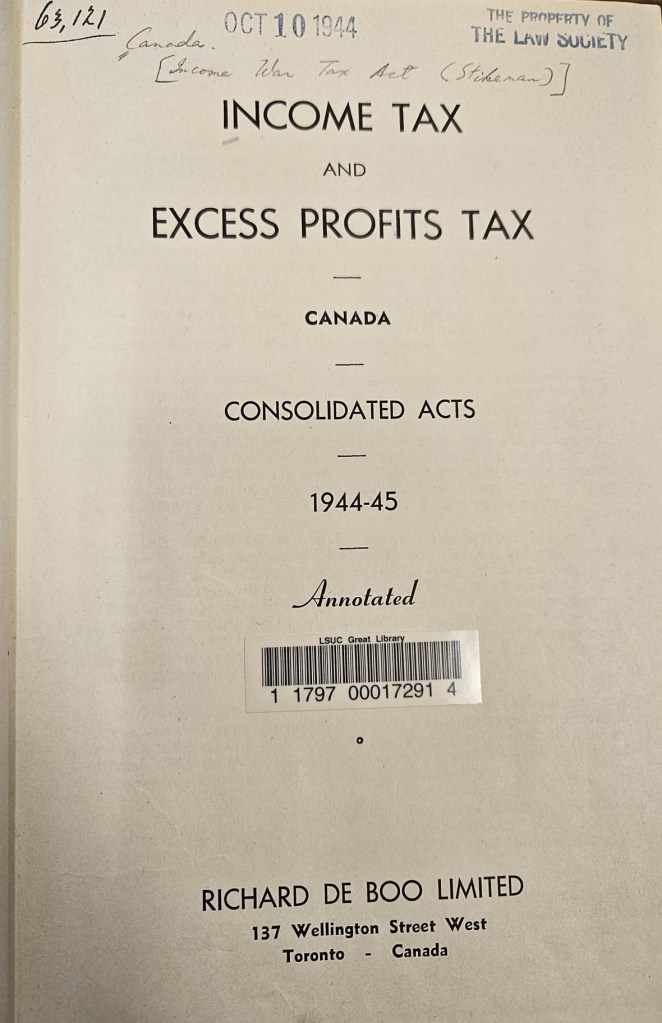

Two publications which frequently have their older editions referenced are Martin’s Annual Criminal Code (1955 – present) and Stikeman’s Income Tax Act Annotated (1944/5 – present). Given the complex nature of both the Criminal Code and the Income Tax Act, tracing back particular sections can be incredibly time consuming. Instead, it is much easier to consult the annual edition of either Martin’s or Stikeman’s to see how the act looked during a desired period of time. These annotated editions also come with extra information that is not available in the original act, such as legislative histories, citing case law, and citations to documents like instructional bulletins.

So, the next time you’re faced with a challenging question, remember: there’s plenty of wisdom to be found inside those musty old books – the answer you seek might just be inside.

Discover more from Know How, the blog of the Great Library

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.